Sega has always felt like the industry’s perpetual underdog, operating on a frequency slightly different from its peers.

From its arcade-first roots to its sheer willingness to gamble on hardware that was years ahead of its time, the company’s path was never a straight line. It wasn’t born from a mascot or a toy-making background; it was born from a specific moment in post-war Japan where opportunity met a very practical need for entertainment.

In the years following World War II, Japan’s entertainment landscape was changing rapidly. Coin-operated machines became a practical business in areas shaped by an American military presence, creating demand for amusement that sat somewhere between novelty and routine. It was within this environment that the foundations of Sega were laid, first as a service operation and later as a formalized entertainment company.

The name itself reflects that practical origin. “Sega” is derived from Service Games, a company established to supply coin-operated amusement machines to U.S. military bases in Japan. The shorthand was not conceived as a brand in the modern sense. It was functional and flexible, qualities that mattered more than personality at a time when the industry had yet to define itself.

From Service Games to Sega Enterprises

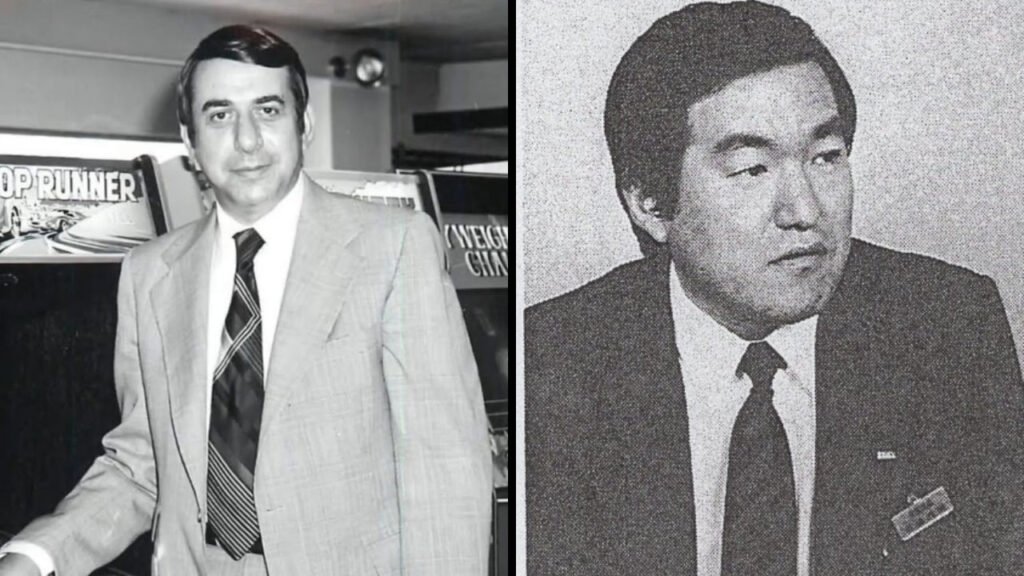

One of the figures central to that transition was David Rosen, an American businessman operating in post-war Japan. Rosen founded Rosen Enterprises in 1954, building a photo booth and coin-operated amusement business. In 1965, Rosen Enterprises merged with Nihon Goraku Bussan, the Japanese arm of Service Games, forming Sega Enterprises Ltd. Rosen did not originate Service Games, but he became the executive force that structured and expanded the newly consolidated company beyond its original military-base focus.

That continuity mattered. The Sega name carried forward not as reinvention, but as evolution. What began as a narrowly focused operation retained its emphasis on function while gaining the flexibility to grow. Sega was built to operate before it was built to express, and that distinction shaped its early direction.

The Arcade-First Mindset

From that foundation, Sega’s trajectory remained closely tied to arcades. The company expanded its presence in coin-operated entertainment at a time when arcades functioned as social spaces and testing grounds. Hardware limitations were immediate, player feedback was direct, and success or failure was visible almost instantly. That environment rewarded iteration and risk in ways home entertainment did not.

Sega’s early machines reflected that reality. They were designed to attract attention and justify repeat play. This arcade-first mindset became a defining trait, one that continued to influence the company long after it entered the home console market. Sega approached games as experiences meant to be felt quickly and remembered clearly, a philosophy shaped by years of operating in public, competitive spaces.

As the industry matured, Sega evolved beyond its original scope. Leadership changed, markets shifted, and the company’s ambitions expanded into consoles and publishing. The Sega that released hardware and cultivated arcade staples like OutRun and Virtua Fighter was not the same Sega that began as a service operation, yet it remained connected to that origin. The structural decisions made early on continued to inform how the company navigated growth and risk.

That continuity also explains Sega’s comfort with operating outside conventional expectations. The company often moved faster than its peers, sometimes at the cost of stability, other times to its benefit. Those tendencies were not anomalies. They were extensions of a business shaped by immediacy and adaptability from the start. With distance, these patterns become easier to trace. As the figures who helped establish the modern games industry pass from view, history risks being reduced to brands and products alone. That approach flattens the conditions and decisions that allowed those brands to exist.

David Rosen’s passing marks the loss of one of those foundational figures. His role was not defined by individual games or creative direction, but by helping establish a company positioned to grow, adapt, and endure. Sega’s identity has been rewritten many times since its founding, but the framework that allowed those changes remains intact. Understanding how Sega came to be does not require nostalgia. It requires context. At moments like this, revisiting origins is less about looking back fondly and more about seeing clearly how the present was built.

The Engineering of an Era: Hideki Sato

This transition from service to expression was made manifest through the hardware engineering of Hideki Sato. While Rosen established the company’s structural capacity to grow, Sato, who passed away on February 13, 2026, designed the systems that defined its output. As the principal hardware architect overseeing Sega’s home console development from the SG-1000 through the Dreamcast, Sega’s final console, Sato’s work was about more than just silicon and plastic.

His engineering wasn’t just about raw power; it was about creating hardware that could replicate the immediacy of the arcade, like the frantic momentum of Crazy Taxi or the visceral intensity of House of the Dead, within the constraints of consumer electronics. Understanding the impact of David Rosen Sega fans still feel today is inseparable from Sato’s physical designs. Rosen provided the opportunity, but Sato was the one who built the machine.

Further Reading & Viewing

Video: Remembering David Rosen – A look back at the life and legacy of the man who co-founded Sega Enterprises.