In today’s gaming landscape, remakes are everywhere. As publishers revisit classic titles with modernized visuals and systems, questions around preservation and creative legacy are becoming harder to ignore.

Remakes have become increasingly common across the modern games industry. From Resident Evil 2 to Final Fantasy VII, publishers are revisiting their back catalogs with sharper visuals, modernized mechanics, and renewed marketing pushes aimed at longtime fans and new audiences alike. These releases often generate excitement, but they also raise an important question: are remakes preserving what made these games meaningful, or are they reshaping them into something fundamentally different?

What Should a Remake Be?

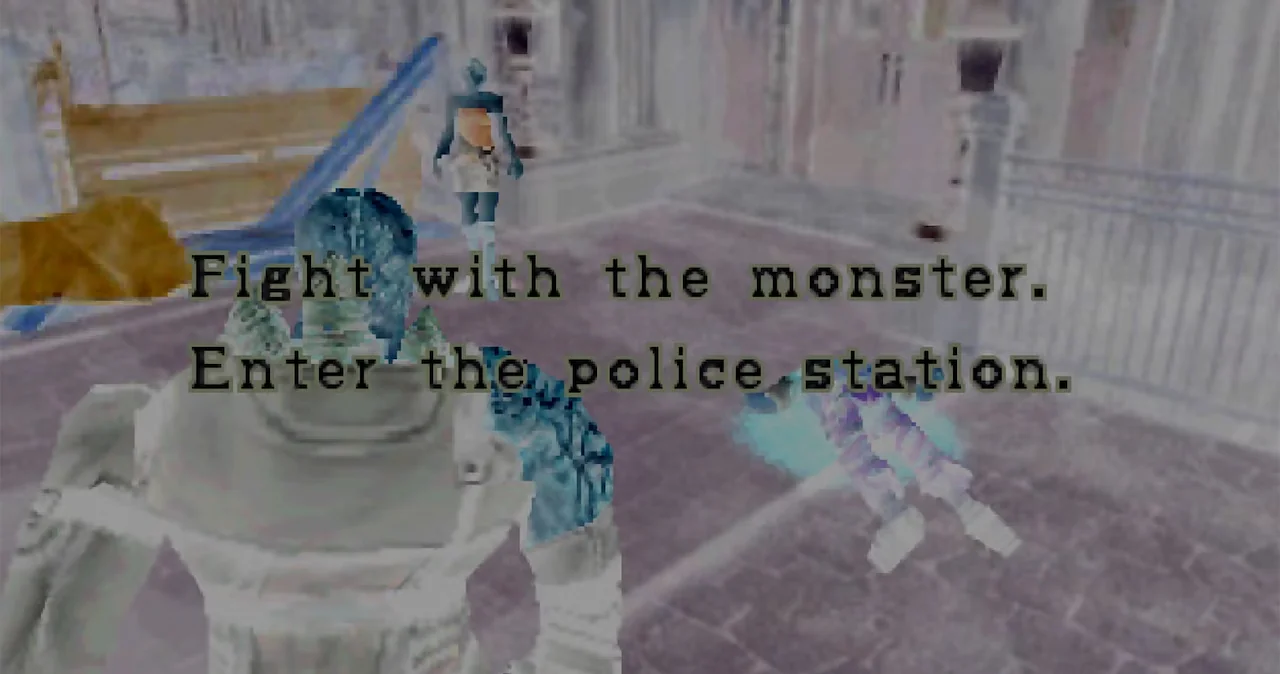

At their best, remakes offer an opportunity to overcome the technical, financial, or design limitations of an earlier era. Hardware constraints, rushed development cycles, or incomplete original visions can all be addressed with modern tools. A title like Parasite Eve II, constrained by its production timeline, could benefit from a remake that fully realizes its ambitions while respecting its identity.

The strongest remakes do more than update presentation. They elevate the original by retaining its tone, structure, and intent while embracing modern capabilities. When successful, they feel familiar without feeling outdated, and new without feeling disconnected from their roots.

However, not all remakes reach that standard. In some cases, content is removed, systems are simplified, or thematic edges are softened to align with contemporary expectations. When this happens, the result can feel less like a restoration and more like a revision. A remake should reconstruct and enhance the original experience, not hollow it out in pursuit of broader appeal.

Defining the Terms

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they describe very different approaches:

- Remake: A remake rebuilds a game from the ground up while honoring its original design, tone, and structure

- Reimagining: A reimagining uses the original as a foundation but significantly alters story, pacing, or themes.

- Remaster: A remaster enhances an existing game through improved resolution, performance, or minor refinements while largely preserving the original code.

This distinction matters because expectations change depending on which approach is being taken. This article focuses on remakes as faithful rebuilds, not reimaginings or remasters.

Resident Evil (2002): A Benchmark

Resident Evil 2002 proves that rebirth can still feel familiar.

Capcom’s Resident Evil (2002) for the GameCube remains a clear example of a remake done right. Compared to the 1996 original, it feels immediately familiar while benefiting from modernized visuals, refined controls, and smarter enemy behavior. The series’ B-movie tone is preserved, but its delivery is more confident and cohesive.

Crucially, content cut from the original was not discarded but expanded. New areas, deeper lore, and systems like Crimson Head zombies reinforced tension without undermining the original design. The result feels less like a replacement and more like a definitive edition, one that honors the past while standing confidently on its own.

While Resident Evil (2002) set a high standard, not every high-profile remake has followed the same philosophy. Examining where others diverge highlights why terminology and intent matter.

Remakes and Reimaginings

Cloud and Aerith’s iconic church moment reimagined in the remake.

Final Fantasy VII Remake is better understood as a reimagining rather than a traditional remake. It builds on the original’s foundation while reshaping its story, pacing, and structure into something fundamentally new. The relationship is similar to that of Disturbia and Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window: the core idea remains recognizable, but the execution, tone, and intent differ enough to create a distinct experience. Some players welcome this expanded approach, while others feel it moves too far from the original’s focused narrative. When projects like this are labeled as remakes, mismatched expectations are almost inevitable.

What Gets Lost in Reimagining

The distinction between remakes and reimaginings becomes more consequential when changes begin to remove or replace defining elements of the original experience. Later Resident Evil entries illustrate how this shift can reshape not only gameplay, but historical context.

RE3’s live selection system made panic part of the design.

Resident Evil 2 (2019) modernized combat and presentation while reworking enemy behavior and campaign structure. While visually striking, its revised systems introduced issues such as inconsistent enemy interactions and a simplified A and B scenario structure compared to the 1998 original. The result was a compelling reinterpretation, but one that altered how tension and player choice functioned across multiple playthroughs.

Resident Evil 3 (2020) moved even further in this direction. Many of the original’s player-driven moments were removed or condensed. Branching encounters with Nemesis, environmental choices that allowed players to escape or confront threats, and entire locations such as the clock tower were cut entirely. What remained was a faster, more linear action experience that retained the broad outline of the original story but discarded much of its systemic depth.

Even when technically competent, these changes represent design ideas that may never return. When remakes replace originals rather than coexist with them, those ideas are effectively lost to time.

Not all modern revisions follow this path. Resident Evil 4 (2023) demonstrates a more balanced approach, staying closer to the original’s tone and narrative while updating combat systems for modern expectations. Shadow of the Colossus (2018) offers an even clearer example of restraint, modernizing visuals and controls while preserving the ambiguity, atmosphere, and emotional weight that defined the original experience.

Preservation and Revision

Many classic games remain inaccessible on modern hardware or disappear from digital storefronts entirely. Remakes and remasters could serve as preservation tools, but revisions made to align with contemporary standards often reshape meaning rather than preserve it.

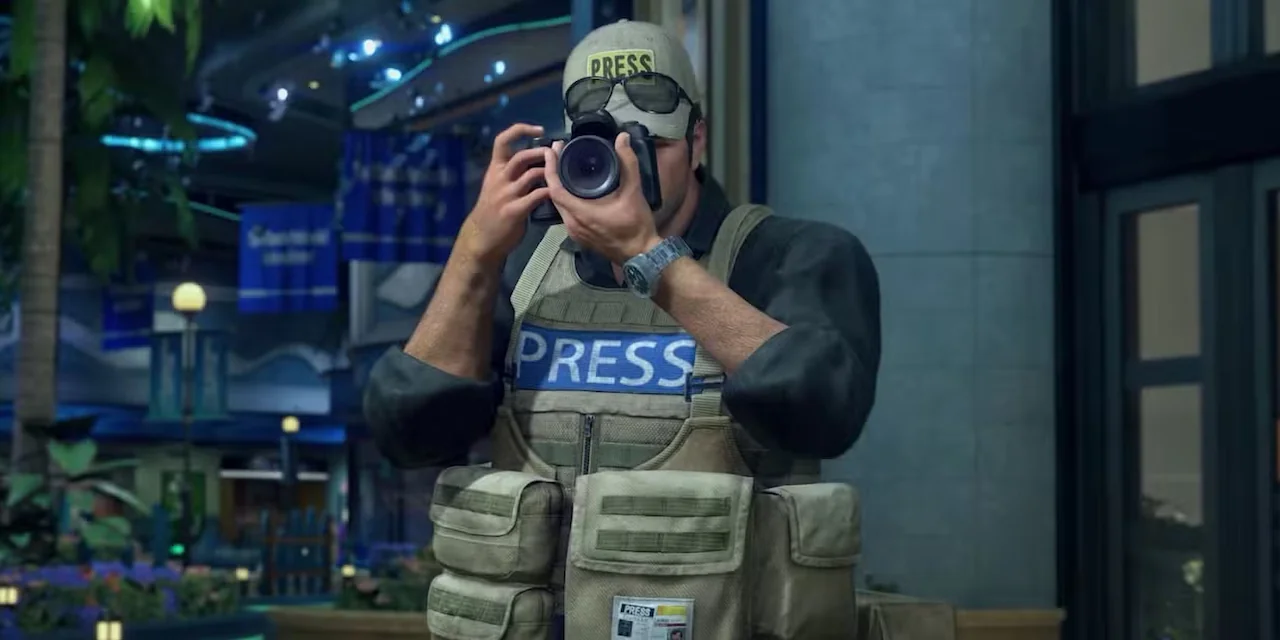

Frank West’s satire took a hit when the camera lost its edge.

Dead Rising Deluxe Remaster (2024) adjusted dialogue, mechanics, and visual framing that were originally designed as satire of sensationalist media.

The remake trades tension for restraint.

- Silent Hill 2 (2024) altered character design choices that played a central role in the original’s psychological tension.

These changes, regardless of intent, influence how new audiences interpret these works.

When original versions are unavailable, revised editions become the only accessible record. At that point, preservation gives way to replacement.

A Second Chance, Not a Rewrite

Remakes should be opportunities to revisit creative history, not overwrite it. When handled with care, as demonstrated by Resident Evil (2002) and Shadow of the Colossus (2018), they can introduce classic games to new audiences without compromising their identity.

Providing access to original releases alongside remakes would offer choice and context. It would allow players to understand how and why these games mattered, rather than experiencing only revised interpretations shaped by modern priorities.

Final Thoughts

At their best, remakes honor the vision, structure, and tone of the originals while addressing the limitations of their time. When that balance is respected, remakes can bridge generations and preserve gaming history.

When it is not, the industry risks losing more than old games. It risks losing an understanding of how those games shaped the medium in the first place.